On a hot Chicago Saturday in June, while tourists snap pictures of the Chicago Theater marquee, I’m making my way through the unassuming cinema entrance across the street to attend a day of screenings at the Gene Siskel Film Center. With all respect to my favorite Chicago cinema—my “happy place”—the Music Box Theater, the Siskel is the cinema I think of when it comes to my all-time favorite movie experiences. The screenings are perfection—the sound and image cared for in a way that practically swaddles the audience. The decline of attention to the primary purpose of a cinema—to get the image to the screen and the sound to the audience—is all but secondary to most multiplexes these days. As much of a champion as I am of collective moviegoing, I understand why many balk at it. Projection has become a degraded art. A typical AMC is just as likely to botch a screening as they are to get it right. On numerous outings I’ve sat well into horrendous projections while the audience, seemingly naturalized to the multi-plex experience being just a bit shitty, just sat there. When this happens I usually go ask for a pass to something else and hope for better next time—and a few times even that second screening has failed to redeem itself in terms of mere technical function.

Also, it’s too damn expensive.

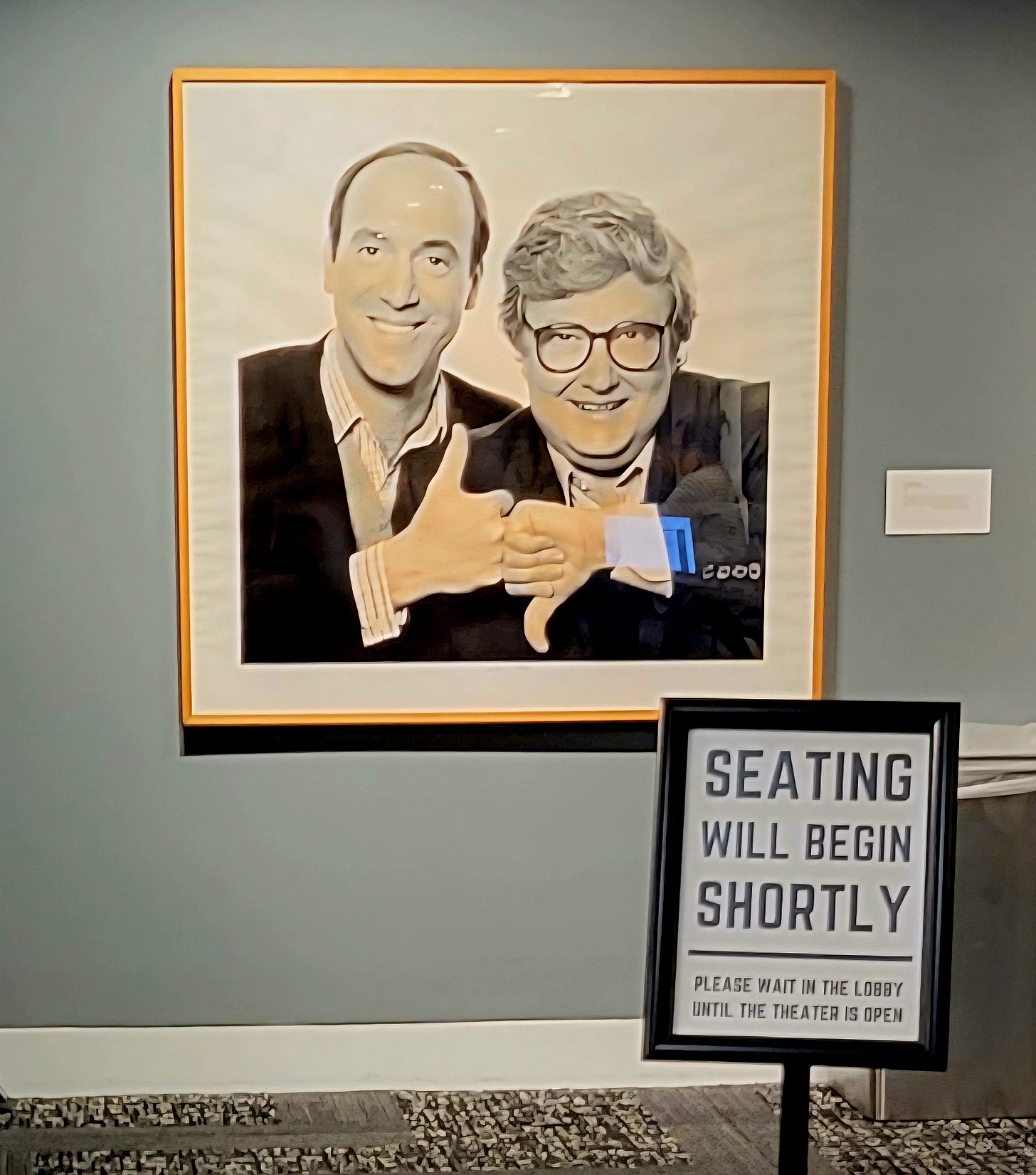

Fortunately, there are still cinemas that behave as if they were the home for some potential sacred happening. Such is the Gene Siskel Film Center. I noted the impact of Siskel and Ebert as critics at the beginning of a detour-filled review of one of my favorite films of last year, Victor Erice’s monumental Close Your Eyes, and it’s difficult not to ruminate, once again, on their controversial status in the film world while attending screenings at the Siskel. There are those who still say that the critical duo’s indelible metric of “thumbs up/thumbs down” is a blight on the history of criticism. Of course, they were serious and important critics beyond those simplistic gestures, and the first to televise nuanced conversations about film that were nothing short of a cultural shift. It’s impossible to walk into either Cinema 1 or Cinema 2 at the Gene Siskel Film Center—164 N. State St. in Chicago—without thinking about all this. This rather large photo guides the way:

My most memorable screenings at the Siskel? Primary among those would be the three separate years I saw Tarkovsky’s Stalker. The screening in 2011 featured assistant cinematographer on Stalker Gregory Verkhovsky explaining to us an astonishing bit of information about the production I’d never heard recounted: due to disastrous processing failures the entirety of the film was shot three times. The Stalker we know, in other words, is the third try. The lingering questions of what the film would have looked like if version one or version two had been the surviving print has been a tantalizing notion for me ever since that night. The film itself is still one of the rare experiences that not only mesmerizes, but seems to defy perceptual laws.

On another occasion, F.O.E. (Friend of ECSTATIC) Brian Morgan and I saw another Strugatsy Brother’s adaptation, Aleksie German’s indescribable Hard To Be a God. Neither one of us were quite sure what we’d just seen. Hard To Be a God is, perhaps, the film experience that leaves one feeling most like they’ve witnessed an artifact from another planet. And Brian and I have watched a lot of strange shit together (and probably too many Jean Rollin movies), but I don’t recall any movie chewing us up and spitting us out, so to speak, like Hard To Be a God. And at the Siskel it was appropriately disorienting—a swirling assault of sloppy, oily, belching, muddy momentum. It’s the kind of screening that was so impactful I wouldn’t dream of watching it at home—only another screening at the Siskel would suffice.

Another FOE and cinephile/video maker, Husni Ashiku, joined me for Godard’s Goodbye to Language in 3D. Not unlike Stalker, perceptual principles were deeply challenged. Godard split our vision in two and continued his singular late career project of tearing apart most viewer assumptions about what to expect from a cinematic experience. I would never claim to have Godard figured out, but the glimpses of insight I’ve gained along the journey of watching his films have sometimes been revelatory, even when the films aren’t particularly good or accessible. Goodbye to Language at the Siskel was nothing short of revelatory, and one I think about often.

The Siskel contains multitudes, as it were, and the array of memorable screenings are too many to fully recount: Akira Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood, Carol Reed’s Odd Man Out, Hiroshi Teshigahara’s Antonio Gaudi, and Bill Morrison’s Dawson City: Frozen Time come to mind most immediately.

On this particular Saturday I sat next to a woman who seemed to live nearby and came to the Siskel often. I’m coming up from southern Illinois, so I’m a bit envious. The five hour journey is usually more like six when you include the task of parking. As we talked before one of the screenings I asked what she had seen recently that she really liked. She came so often that she couldn’t recall… “something about a woman who won an award for her writing…I see so much here I can’t remember.” I bristled a bit as we sat through movie, envious of her close proximity to those seats.

After a few rustling moments of the audience settling, the movie swept me up. It was one I had seen years ago at home and liked well enough, but never really understood why it was quite so highly regarded. After the 35mm print at the Siskel, I think I understand.

McCabe and Mrs. Miller

Robert Altman, 1971

Roger Ebert wrote in 1999: “Robert Altman has made a dozen films that can be called great in one way or another, but one of them is perfect, and that one is McCabe & Mrs. Miller.” He goes on to perfectly characterize the films as “a poem–an elegy for the dead.” For me this brings to mind the other significantly subversive western of this period, Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garret and Billy the Kid (F.O.E. Keith Nainby and I unpacked that film thoroughly here), which is not only a similarly revisionist Western, but a film whose script is littered with the names of characters we’ve never met—the dead that lay in the wake of the violence Peckinpah was known for crafting in such cinematically distinct ways.

Robert Altman is not interested in violence in the same way Peckinpah was, but the sense of melancholic reflection that occurred in the period that traverses both films links them, marked by the similarly elegiac singer-songwriter scores woven into each: Bob Dylan for Pat Garret and Billy the Kid, Leonard Cohen for McCabe and Mrs. Miller. By the time there is an actual “western” shootout in McCabe and Mrs. Miller, it’s perhaps the saddest and most resonant shootout ever committed to film. Keith Carradine plays a young man who has come to a half-built town for the whores. His character is the cliche of “a lover not a fighter,” but Carradine plays past the cliche, and the way the script reveals his vulnerability leads us to his demise. Meanwhile, the spoken cliches of Beatty’s McCabe wear thin as the walls grow around him, and what they represent threatens to envelop him.

Eventually, it’s the snow that envelops McCabe, a visual motif Altman would return to later in the 70’s with Paul Newman and the science fiction film Quintet. Along the way Altman would slip in and out of his “revisionist” mode, controversially moving Raymond Chandler’s The Long Goodbye into the 70’s with Elliot Gould and examining the theatrics of history (again with Paul Newman) in Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull's History Lesson. All of these films are beautifully crafted and shot, though only The Long Goodbye and McCabe and Mrs. Miller were shot by the great Vilmos Zsigmond. It’s impossible to walk away from McCabe and Mrs. Miller without a deep impression of how uncannily Zsigmond captured his subjects in relation to the nature that surrounded them. The lingering effect of the film is inseparable from it’s sense of the natural world and the brutal shift of seasons.

Sabbath Queen

dir. Sandi Simcha Dubowski, 2024

Sabbath Queen was not a planned screening this particular Saturday of Pride month, but I’m lucky to have taken a chance on squeezing this one in. Also, I’m partial to going into films blind, which is how I experienced this very moving, decades-spanning documentary about Rabbi Amichai Lau-Lavie, a member of the Radical Faeries collective, creator of the drag persona Rebbetzin Hadassah, and a descendant of 38 generations of Orthodox rabbis. As an unexpected surprise (to me, at least), Lau-Lavie and Dubowski were in attendance to take questions after the screening. Dubowski’s commitment to documenting Lau-Lavie was exhaustive, but the ultimate scope of the film is concise. Clearly, Dubowski could have created a much longer piece on Lau-Lavie and his performance art approach to Judaism, but one of his great achievements here is understanding that the ideas are what need to radiate and expand, not the run time.

With that said, there is less about drag than the publicity for the film might suggest. And this is to the film’s benefit, because what feels essential about Sabbath Queen goes beyond a celebration of drag, though drag is an essential component to understanding Lau-Lavie’s progressive practice. A large part of that practice is centered around his invention of “Lab/Shul”—an artist-driven, everybody-friendly, God-optional, pop up, experimental community for sacred Jewish gatherings based in NYC. The narrative of the documentary is partially framed around Lau-Lavie’s Rabbi status being threatened by his commitment to pluralist practices of faith, particularly his decision to marry two Buddhist Jewish men who want to include Eastern ritual in their union.

In a time when the violence in the Middle East rages on—and on the day of the US bombing of Iranian nuclear facilities—stumbling into this screening was an education and a confluence of community, healing, and understanding. Celebrating the Siskel is not just about a place, but the larger connection we establish to the world through movies. Sabbath Queen deals with faith and the conflict in the Middle East in ways that I simply understand more clearly having seen this film. Between No Other Land from earlier this year—an absolute must-see for those wanting perspective on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict—and Sabbath Queen, my sense of the world feels gratefully elevated above the polarizing media sludge (which I lap up way too often). And it’s not just leaving with “hope” or a feeling of patting myself on my liberal back for having attended the right whatever. I’ll be the first to admit that I’m a dummy when it comes to the Middle East, and have little insight when it comes to how Orthodoxy and religious practice are so entrenched in the violence we hear reported—or turn away from—every day. What Sabbath Queen brought into focus was how pluralist ideologies light a potential path to anti-violence that can break down borders. I don’t have hope this will happen, but these are the principles I believe in as sentiments of acceptance and inclusion face the threat of increased absence from the spiritual and media landscape.

Find out more about Rabbi Amichai Lau-Lavie and Sabbath Queen—where you can catch it or book your own screening—here: https://www.sabbathqueen.com/

BOOM!

Joseph Losey, 1969

In 2011, not long after the death of Elizabeth Taylor, Jen and I were fortunate enough to spend some time in San Francisco. Jen’s work had taken her to a conference there, and that summer I drove from New Jersey to San Francisco, and then we road-tripped all the way back to our home in Michigan. While in San Francisco we randomly ate at what we concluded was somehow the worst Mexican restaurant in the city, if not the entire west coast. On the more awe-inspiring side of the trip, we crossed the bridge and walked through the towering Muir Woods. But the question still remained: which looms larger? The trees of Muir Woods, or the projections of Elizabeth Taylor at the Castro Theater? That question hung in the air as we watched Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? at the Castro’s Elizabeth Taylor retrospective. It’s difficult to recall a time I’ve been in a more appreciative audience of cinephiles—even though Liz was the focus, every billed actor received a round of applause as their opening credit rolled, as did cinematographer Haskell Wexler and director Mike Nichols.

But the movie that goes unseen is typically the one I’m most interested in, and that day at the Castro featured a Taylor/Burton double bill of Woolf and a movie with a most intriguing title that we didn’t have time to catch. In fact, I hadn’t heard of this particular B-side until that day, and the title was so distinct it travelled back across the country with me: Boom! Since then I’ve run across the title here and there, but never looked into it closely. It’s rarely screened, and it turns out to be directed by Joseph Losey whose films I’ve gotten to know much better in the intervening years—his 1963 film The Servant with Dirk Bogarde is of particular note. A couple of others I was unsure what to make of, but still struck by their curious construction and Losey’s signature sense of blocking and framing, objects and architecture—Accident (1967, again with Bogard) and another Liz Taylor film around the same time as Boom!—this time opposite an astoundingly uninvested Robert Mitchum—Secret Ceremony.

Depending on where you see Boom! listed, the title of this 1968 Tennessee Williams script involving a reclusive diva on a Mediterranean island being visited by the “angel of death” might be published without an exclamation point, but make no mistake…Boom! is a movie that needs an exclamation point in the title! When I first saw the title on the Castro marquee my imagination went to some romantic story possibly involving dynamiters or mining, but the “Boom!” of the title refers to the relentless crash of waves on the rocks that surround the isolated isle that belongs to Flora Goforth (Taylor). She is visited by a poet she may or may not recognize named Chris Flanders (Burton) who is nearly torn to shreds by her guard dogs, commanded by Rudi (Michael Dunn) her sinister dwarf security guard. Rounding out the cast are Miss Goforth’s lamenting lackey Miss Black (Joanna Shimkus) and a visitation by the Witch of Capri (the king of Brit Pop himself, Noël Coward).

Burton was criticized at the time for being too old and miscast. Today that miscast seems almost essential. Burton’s character declares himself “the angel of death” to the ailing Goforth and increasingly repeats the titular refrain whenever he hears the crashing waves:

“Boom! The shock of each moment of still being alive.”

(Can’t you just hear it in Burton’s voice?) He comically spends almost the entire movie in a samurai outfit holding onto a sword hilt phallus—the outfit chosen by Miss Goforth—and the interplay between Liz and Dick is ultimately what makes the movie so compelling and absurd, and one of the more elevated gems of expressionist camp. For instance, Burton reflectively, appropriately recites the opening to Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan”:

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan/ a stately pleasure-dome decree:/Where Alph, the sacred river, ran/through caverns measureless to man/down to a sunless sea.

Taylor responds in the most hilariously put-upon and exasperated Liz Taylor way possible:

“WhaaAAAT?”

Although the film was a failure in ‘68, Williams considered it to be the best screen adaptation of one of his plays. The Siskel programmed Boom! as part of their “Summer Camp” series for Pride month, and the comedy and overwhelming “Liz-ness” of it all played like gangbusters. I predict this one will gain wider and wider appreciation in repertory screenings, and it deserves it.