Back in 2011 I was going through some transitions in work and life. I had been teaching theater, speech, and film for ten years at the same institution, and moved with my partner to Michigan that summer. While I loved teaching a general education course in cinema appreciation, after five or six years the repetition of leading students toward methods for writing critically left me wanting time to refine my own critical skills. As you might imagine, in my course some of the writing was geared toward films that I would assign, and others were geared toward films that students were enthusiastic about and would get to chose as a topic for themselves. While I might like a go at teaching the course again (and would surely teach it very differently now), I’m not sure I need to read another student paper commenting on how bothersome the subtitles were in Bicycle Thieves, or how awesome Zack Snyder’s 300 was. This was not the norm, of course (although I did read a lot of papers about 300). Many of my students had a high level of critical acumen, and a few still work in the business of making images and art in various modes, so I send all my best to them in hopes that they continue creating and conversing with the arts in their own way. Meanwhile, I’m still trying to carve out a sentence or two in the same pursuit, still listening to that muse Werner Herzog intoning his theory of the ecstatic.

When I started writing the ECSTATIC Film blog in August of 2011, I quickly borrowed the title from one of the filmmakers I was most enthusiastic about at that time and dove in. The goal was little more than to create a consistent writing habit for myself, and I though I’ve faltered (and altered) in that practice over the years, I’m content with now moving toward two years of consistent self-publishing on the new site, ECSTATIC Screen Notes. I’d like to share that first 2011 post with you as we head into August almost 13 years later. It seems appropriate that the film was Herzog’s The Cave of Forgotten Dreams for a number of reasons. I’ll let the article speak for itself, and offer up a few reflections upon re-visiting this piece: 1) My style and voice has changed a bit, hopefully. 2) I’m still a terrible critic of my own writing and feel satisfied with only a few things I’ve ever written…and fully expect to be dissatisfied with those in the near future. 3) Traditionally, there’s a distinction made between “reviews” and “criticism.” I’ve tried to resist either/or thinking about writing modes and simply follow what seems right or interesting to me. 4) The same potential for ecstatic truth still drives my critical engagement with the image. It’s not the only thing, but it certainly marks some of the best glances I’ve had at the cave wall.

With that, I officially say farewell to the old blog. With some reservation, here’s the first post from 8/8/2011.

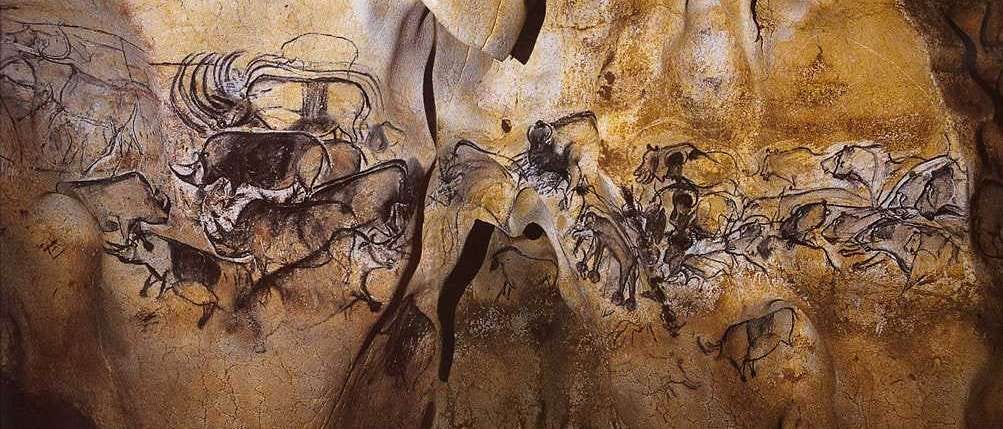

Werner Herzog's new 3D film Cave of Forgotten Dreams is a continuation of the master director's search for new images, the "ecstatic truth," and connection with the spirits of the past. In his latest adventure the Bavarian earth-walker takes us to what may be the most awe-inspiring location he has explored and translated through film thus far: the Cave of Chauvet Pont-d'arc in southern France.

Ranking the enormity of Herzog's discoveries is no easy task, considering his last feature documentary, 2007's Encounters At the End of the World, took the viewer to Antarctic depths never before recorded on film. The deep ocean photography alone in Encounters could support an entire film, but as with many of Herzog's journeys, the film features a captivating centerpiece made truly ecstatic by all that Herzog captures and develops around it: the voices of experts and outsiders, the bold scoring choices that weave in and out of the foreground, and the unexpected breezes and pauses. Herzog loves those small moments after the interview, after the intended shot, that often reveal multitudes.

Another difficulty with addressing Herzog's work is the use of the word "documentary." The border between fiction and non-fiction is one he takes pride in ignoring. For instance, in Lessons of Darkness (1992) Herzog approaches his exploration of a post-Desert Storm Kuwaiti landscape as an alien, his voice-over script asking puzzled questions about a strange, strafed land. As in The Cave of Forgotten Dreams, the examination of the focal centerpiece is meditative, searching. Herzog knows the weight of his subject, and allows us to examine his images deeply, often until we have completed a cycle of perception that allows us to see them with new, alien eyes. Herzog does not call Lessons of Darkness a Documentary, but Science Fiction.

For some, Herzog's disregard for the genre conventions of documentary filmmaking are too brazen, particularly those who have bought into the forms of modern documentary as a conduit for "facts," built on communicating an agenda that Herzog interprets as a facile, "bean-counter's" truth. Herzog does not try to prove through his films, but provoke. For instance, it is not uncommon for him to invent scenes, behaviors, or occurrences within a documentary film to coexist alongside the naturally occurring events he captures. In his 1998 film Little Dieter Needs to Fly, he requested that his documentary subject, former prisoner of war Dieter Dengler, behave as if he were now obsessed with doors and door knobs as a psychological result of his imprisonment. Having developed an agreeable relationship with the film maker, Dengler complied. Likewise, it is not uncommon for Herzog to follow the paths of what is really happening within a so-called fiction picture (as with his wandering fascination with amphibian, reptilian, and free-roaming Coppola-based life forms in his recent oddity Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans). Even though I tend to "cross the line" with Herzog in those moments where some critics might throw up their hands and scoff (we'll get to the albino alligators in a moment), I have to say that his most seen film, 2005's Grizzly Man, contains scenes of uncomfortable falseness for me, created by Herzog's drive to create an estranged moment at any cost; those moments where an interview subject appears uncomfortable in their directed role, in many cases apparently re-performing a version of themselves. Similar moments exist in Cave of Forgotten Dreams, as when he asks Maurice Maurin, a master perfumer, to exhibit his keen knack for sniffing out hidden caves. Also, there are moments where the gap between Herzog's voice-over script and the profundity of the image are stretched to the max (we'll get to the albino alligators in a moment). Still, it is this leap of faith across the borders of fiction and non-fiction that makes a film like Grizzly Man one of the most unique and important documentaries of our time.

In this border-crossing with Herzog, we find some important philosophical differences to weigh when viewing his work. In the 2008 documentary Capturing Reality, some of the greatest current documentary filmmakers are questioned about such philosophical positions. In the film, Herzog states that "the distinction between narrative feature films and documentaries doesn't exist that much...for me it's all movies." Capturing Reality places this notion of truth in documentary film in direct opposition with another giant of the modern documentary, Errol Morris (The Thin Blue Line, 1988; First Person, 2000 [a sadly under-seen TV series aired on Bravo]; The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons From the Life of Robert S. McNamara, 2003; Standard Operating Procedure, 2008.)

Much has been made about the tension between these two documentary greats (going all the way back to a wager that resulted in the 1980 Les Blank short film Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe...in which Herzog does just that), and it is true that their techniques are as vastly different as a Realist and an Absurdist. But, like the Realist, Morris finds truth through his relentless conviction that there is a specific, unwavering truth in the events that he is examining; that there is something that happened. And Herzog, as he repeats, re-frames, and re-lights the images of the Chauvet Cave in the final passages of his new film, is the Absurdist who yawns at the idea of the cold search of the Realist, repeating once again the passage we have seen before as a way to, hopefully, see it as if for the first time.

Cave of Forgotten Dreams is also a continuation of Herzog's stand against "used up" Hollywood images. In some ways, there is no more truly independent director than Herzog, as what is often called "indie" filmmaking has recently leaned so aggressively into the light of Hollywood conventions and money. Independent film has lost a sense of risk, and commercial film is now far removed from any aspect of subtlety, patience, nuance. Viewers shifting in their seats in response to some of Cave's more lingering passages are, I would argue, only feeling the pangs of a sweet tooth that is poked at by the increasing domination of commercial cinema's tendency toward relentlessly paced "movie events." These types of films--often presented in 3-D, IMAX, or 3-D IMAX(!)--have left popular movie going in a perpetual state of sugar crash. Cave of Forgotten Dreams is a true event; a film that reaches 30,000 years into our human past, and attempts at all costs to connect the viewer with that common image that links us all.

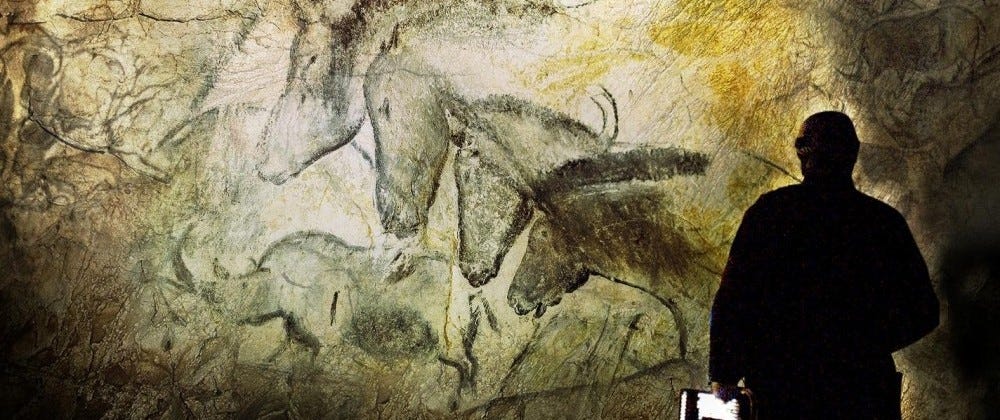

Throughout the first third of Cave, it’s doubtful whether or not this will be as successful an outing for Herzog as his most impressive documentaries (Lessons of Darkness, 1992; Little Dieter Needs to Fly, 1998; My Best Fiend, 1999; Wheel of Time, 2003; The White Diamond, 2004; Grizzly Man, 2005; The Wild Blue Yonder, 2005; Encounters at the End of the World, 2007). It seems that he is more confined in his explorations, literally, as the Chauvet Cave itself is under strict regulations that constrain the filmmakers to only certain parts and paths of the cave. But, these opening sequences are an important part of reading the film overall, as we see how difficult it is for a film like this to take form, and as The Cave of Forgotten Dreams emerges as a film about making films. What at first seems like a clumsy excursion is transformed into an unforgettable privilege of sight as the cameras steady, and we, along with the crew, figure out how to really see the cave.

Some of the most fluid and mysterious moments of the film happen outside the cave, including the opening shot, which takes us along the dry rows of a vineyard and eventually rises out of the vineyard revealing the stunning lakes and rock formations of the Chauvet region. Later in the film a similar shot takes us across those waters and below a natural bridge, the camera pausing mid-air and pivoting below the formations. At a pivotal point toward the end of the film--the moment which most evokes the inevitable allegory of Plato and the cave--we see Herzog reaching up to this camera as it flies into his hands, and the creator of these earlier mysterious images is revealed: a remote-piloted camera plane.

In an age where 3D movie events have so saturated the cinema market, it’s easy to overlook the next camera trick that Herzog is trying out here, and the extent to which he succeeds in heightening our understanding of the potential for 3D images as a serious technique of cinema. Herzog is not only showing us the Chauvet Cave images for the first time, he is showing us 3D cinema for the first time, as well, nearly inverting the relationship we have come to expect. The "reach out and grab ya!" formula of 3-D film hasn't really evolved much since its invention (I clearly remember my first experience with it at a screening in a gymnasium in rural Illinois. The film was The Creature From the Black Lagoon, and the moment of the Creature reaching into the boat, and out to the audience, was the most memorable 3D stunner). From 1950's creature features to Thor and Green Lantern we haven't come far in terms of what 3D cinema asks of us. In Herzog's exploration of the cave, we are asked not to simply thrill at those images that leap out at us—save one of the funniest moments of the film involving spear-throwing, perhaps an intentional nod by Herzog at the silliness of the 3D phenomenon—but rather to experience the textures and contours of the cave walls that helped to create what Herzog likens to an early form of cinematic movement for our ancestors of the cave. As he allows the drawings to play and dance in the various passes of light, the use of 3D doesn't simply jut out at us, but invites us in, asks us to look closely, to take advantage of this privileged mode of seeing. I can only hope that the future of 3D cinema follows Herzog's trailblazing, taking us to more Chauvet Caves, and fewer Asgards.

And, who but Herzog could have given us "Baby Albino Alligator" epilogue to The Cave of Forgotten Dreams? To those critics who reduce it to a strange diversion--or worse--a complete cop-out, I can only wonder what they could have expected. For me, it's the moment where Herzog wakes us from our cinema sleep-walking with the spirit of a surrealist. It's his ability to take us to those unexpected places, and in that perfect moment juxtapose a nearly absurd discovery with all that he has shown us previously. It’s what makes Cave of Forgotten Dreams a documentary that radiates meaning beyond the simple, digestible facts.